Common Causes

Body weight in kg x percent dehydration (as a decimal) = the fluid deficit in ml Body weight in lb x percent dehydration (as a decimal) x 500 = fluid deficit in ml The two categories of ongoing fluid loss include sensible and insensible losses. Sensible losses are those that can be quantified ( e.g. urination).

Related Conditions

Step 1: Calculate Preoperative Fluid Losses Simply multiply the maintenance fluid requirements (cc/hr) times the amount of time since the patient took PO intake. Estimated maintenance requirements follow the 4/2/1 rule: 4 cc/kg/hr for the first 10 kg, 2 cc/kg/hr for the second 10 kg, and 1 cc/kg/hr for every kg above 20.

How do you calculate fluid loss from dehydration?

First 10 kg = 100 ml/kg/day x 10 kg = 1000 mL per day Next 10 to 20 kg = 50 ml/kg/day x 10 kg = 500 mL per day Remaining 50 kg = 20 ml/kg/day x 50 kg = 1000 mL per day Total fluids per day = 1000 + 500 + 1000 = 2500 mL per day

How do you calculate preoperative fluid loss?

Once the degree of dehydration is approximated, the amount of fluid volume required to resuscitate the patient may be calculated. Fluid deficits can be calculated by using the following formulas 5 (1 lb of water = 454 mL; 1 kg of water = 1000 mL):

How to calculate total fluids per day per kg?

How do you calculate fluid deficit in CPR?

How do you calculate total fluid loss?

To calculate the patient's fluid deficit, the veterinarian will multiply the patient's body weight (lb) by the percent dehydration as a decimal and then multiply it by 500.

How do you calculate fluid loss in nursing?

Estimate the percentage of fluid loss based on clinical evaluation. Percentage of dehydration × Weight in kg × 10 = mL fluid needs....Fluid losses normally occurring through the skin, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal (GI) tract.Losses through the kidney system are not insensible losses.More items...•

How do you calculate fluid loss per hour?

Convert any weight loss to ounces or ml of fluid. Check/measure the amount of fluid consumed during training. Add the amount of fluid lost to the amount of fluid consumed to get total fluid losses. Divide the total amount of fluid lost by the number of hours of training to get fluid losses per hour.

What is the 4 2 1 rule for maintenance fluids?

In anesthetic practice, this formula has been further simplified, with the hourly requirement referred to as the “4-2-1 rule” (4 mL/kg/hr for the first 10 kg of weight, 2 mL/kg/hr for the next 10 kg, and 1 mL/kg/hr for each kilogram thereafter.

How do you calculate fluid intake and output?

Subtract the volume in the graduate from the total volume of fluid served to the client. For example, if the volume left in the graduate is 80 mL, this is subtracted from the full serving amount of 700 mL, giving us a total fluid intake of 620 mL (Fig.

How do you calculate fluid intake for adults?

About4 mL / kg / hour for the first 10kg of body mass.2 mL / kg / hour for the second 10kg of body mass (11kg - 20kg)1 mL / kg / hour for any kilogram of body mass above 20kg (> 20kg)

What is fluid calculation?

For infants 3.5 to 10 kg the daily fluid requirement is 100 mL/kg. For children 11-20 kg the daily fluid requirement is 1000 mL + 50 mL/kg for every kg over 10. For children >20 kg the daily fluid requirement is 1500 mL + 20 mL/kg for every kg over 20, up to a maximum of 2400 mL daily.

How do you calculate 24 hour fluid maintenance?

* Maximum maintenance fluid per 24 hours is 2400 mL or 100 mL/hour....Body Wt (kg)Daily maintenance fluid (mL/24 hours)Hourly maintenance fluid (mL/hour)1 to 10100 x Wt (kg)4 x Wt (kg)>10 to 201000 plus 50 x Wt over 10 kg40 plus 2 x Wt over 10 kg>201500 plus 20 x Wt over 20 kg*60 plus 1 x Wt over 20 kg*

What is the formula for calculating fluid deficit for a patient who has been on nothing by mouth NPO status prior to surgery?

FLUID DEFICIT primarily from being NPO for surgery. The classic 4-2-1 calculation (4 cc/kg for the first 10 kilograms, 2 cc/kg for the next 10 kilograms, and 1 cc/kg for each kilogram after) is used to calculate a patient's maintenance requirement per hour. In a 70 kg patient, this would be ~ 110 cc/hr.

How do you calculate maintenance fluids with examples?

Calculating Maintenance Fluids4 ml/kg for first 10kg, 2ml/kg for the next 10kg, 1 ml/kg for every 1kg over 20.For example, for a 70kg person: 4×10=40; 2×10=20; 1×50=50. Total=110 ml/hr.

How do you calculate insensible losses?

Maintenance fluid rate replacement is calculated by using the “4-2-1” rule, which came from the 1950s work published in Pediatrics. [3] For the first 10kg of the patient, fluid replacement is at a rate is 4mL/kg/h. For the next 10kg, the rate is 2mL/kg/h, and for each kg, after 20kg the rate is 1mL/kg/h.

What is a normal IV fluid rate?

Normal daily fluid and electrolyte requirements: 25–30 ml/kg/d water 1 mmol/kg/day sodium, potassium, chloride 50–100 g/day glucose (e.g. glucose 5% contains 5 g/100ml). Stop IV fluids when no longer needed. Nasogastric fluids or enteral feeding are preferable when maintenance needs are more than 3 days.

What is the formula of fluid calculation?

The formula to calculate how many hours will it take for the IV to complete before it runs out is: Time (hours) = Volume (mL) Drip Rate (mL/hour) . The volume of the fluid is 1 000 mL and the IV pump set at 62 mL/hour.

How are fluids calculated in nursing?

1:219:12Calculating IV Drip & Flow Rates for Nurses - YouTubeYouTubeStart of suggested clipEnd of suggested clipOver 2 hours the drip factor is 15 drops per mil.MoreOver 2 hours the drip factor is 15 drops per mil.

How do you calculate insensible fluid loss?

Maintenance fluid rate replacement is calculated by using the “4-2-1” rule, which came from the 1950s work published in Pediatrics. [3] For the first 10kg of the patient, fluid replacement is at a rate is 4mL/kg/h. For the next 10kg, the rate is 2mL/kg/h, and for each kg, after 20kg the rate is 1mL/kg/h.

How do you calculate IV drops per minute?

Add the infusion rate (mL/hour), followed by the time (1 hour over 60 minutes). Cancel the labels. What you are left with are drops (gtts) multiplied by the infusion rate divided by 60. You can rearrange the equation and divide the drops (gtts) by 60 and multiply by infusion rate.

How to calculate maintenance fluid requirements?

Simply multiply the maintenance fluid requirements (cc/hr) times the amount of time since the patient took PO intake. Estimated maintenance requirements follow the 4/2/1 rule: 4 cc/kg/hr for the first 10 kg, 2 cc/kg/hr for the second 10 kg, and 1 cc/kg/hr for every kg above 20.

What is fluid given based on?

Fluids must be given based on an estimation of the following – fluid losses prior to start of anesthesia, maintenance requirements, normal fluid losses that occur during surgery, and response to unanticipated fluid (blood) loss.

What is the classic approach to management of fluids in the perioperative setting?

The “Classic” (read: outdated) approach to management of fluids in the perioperative setting involved trying to predict the amount of fluids needed based on a the duration and severity of a particular operation and empirically replacing fluids based on these estimates. IT IS PRESENTED HERE FOR HISTORICAL INTEREST ONLY AND IS NOT RECOMMENDED.

Why are fluid management studies so confusing?

There are many problems with the fluid management studies of the last century or so, many pointed out by Chappel (see above). Because the vast majority of studies were based on the teleologically flawed, “classical” approach of trying to predict fluid needs, rather than actually measuring fluid needs, it is no wonder that the data are confusing at best. A lack of standardization with regards to what is “restrictive” and what is “liberal” further complicates the data.

Is it safe to give fluids during stroke?

The reality is that fluids can be harmful, and should only be given when they are expected to produce some benefit. Management of fluids such that stroke volume is optimized is an extremely well-validated approach that has been shown repeatedly to reduce morbidity [Hamilton MA et al. Anesth Analg 112: 1392, 2011; Gurgel ST and do Nascimento P Jr. Anesth Analg 112: 1384, 2011]. In fact, esophageal Doppler monitoring (EDM) was recently endorsed by the National Health Service as a rational alternative to central venous pressure monitoring in patients undergoing major surgery. A promising alternative to EDM is optimization of respiratory variation, although it is not as well validated.

Does liberal fluid help with lung function?

Some authors have suggested that liberal fluids improve PONV and tissue oxygenation. Upon reviewing the data, Chappel et. al. state that “ These data, despite being inconsistent, indicate that higher fluid amounts might reduce the risk of PONV and increase postoperative lung function after short operations. Nevertheless, most studies considered only one outcome parameter; therefore, the overall effect on the patient is hard to gauge, because other, potentially more serious parameters may be impacted adversely by the same treatment. These results seem interesting regarding certain collectives, e.g., outpatients during minor surgery, but they cannot account for larger surgery over several hours. Current evidence suggests that liberal fluid is a good idea where major trauma and fluid shifting are unlikely, but more careful fluid management may be beneficial in more stressful operations… ” [Chappel D et. al. Anesthesiology 109, 723: 2008]

Is IV fluid maintenance?

There is essentially no role for “maintenance” IV fluids in modern fluid management – rather, fluids are given as targeted boluses when they are expected to lead to a hemodynamic improvement.

What is the goal of fluid management during perioperative period?

During the perioperative period, the goals of fluid management are to provide a suitable volume of parenteral fluid to support cardiac preload, intravascular volume, oxygen carrying capacity, and electrolyte balance. Additionally, parenteral fluid replenishment focuses on equipping the body with enough fluid to meet both insensible and sensible physiologic losses. Maintenance fluid rate replacement is calculated by using the “4-2-1” rule, which came from the 1950s work published in Pediatrics.[3] For the first 10kg of the patient, fluid replacement is at a rate is 4mL/kg/h. For the next 10kg, the rate is 2mL/kg/h, and for each kg, after 20kg the rate is 1mL/kg/h. Preoperative fasting causes a fluid deficit leading to a slight decrease in the extracellular fluid while maintaining intravascular volume. Without any fluid intake overnight, a patient’s fluid deficit is proportionate to the duration of the fast. This deficit is estimated by multiplying the normal maintenance rate by the length of the fast.[4] Fluid replacement during surgery centers on the type/extent of surgery as well as a patient's hourly needs.

How does the body use water?

The body uses water for a variety of mechanisms from transporting nutrients to excreting wastes and tissue structure viability. Water balance occurs by matching the daily water input/output to and from the body. The primary means of water intake is by consumption of food and fluids. Daily fluid maintenance requirements for adults are approximately 1.5 to 2.5L of water.[1] The majority of fluid loss occurs in urine, stool, and sweat but is not limited to those avenues. Insensible fluid loss is the amount of body fluid lost daily that is not easily measured, from the respiratory system, skin, and water in the excreted stool. The exact amount is unmeasurable but is estimated to be between 40 to 800mL/day in the average adult without comorbidities.[2] A total loss of approximately 600 to 800mL/day characterizes 30 to 50% of all water loss, contingent on the level of water consumed. Thus insensible water loss is a significant component of water balance and needs to be routinely monitored.

How to determine fluid status?

Often, one can determine the patient’s fluid status clinically based on a variety of physical exam findings and objective data from their vital signs. Laboratory markers are helpful as adjunctive data. The following is a list of findings that can help determine whether a patient is fluid-depleted or volume overloaded. [1]

What is fluid management?

Fluid management is a critical aspect of patient care, especially in the inpatient medical setting. What makes fluid management both challenging and interesting is that each patient demands careful consideration of their individual fluid needs.

What is the difference between maintenance fluids and fluid replacement?

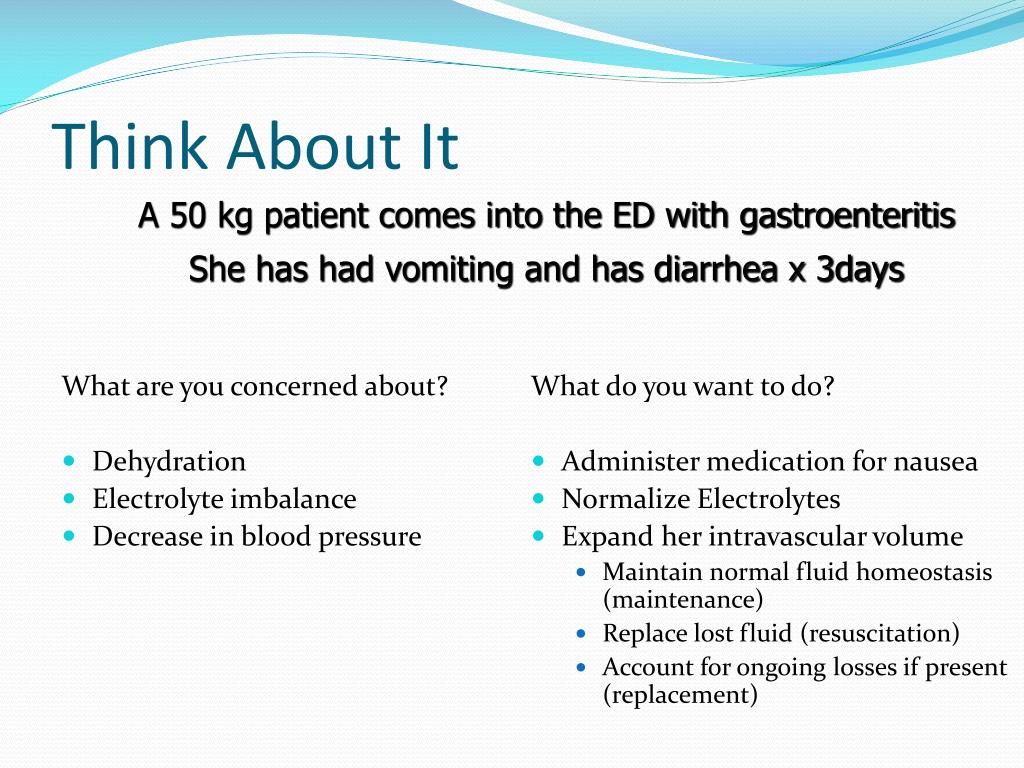

Maintenance fluids should address the patient's basic physiologic needs, including both sensible and insensible fluid losses. Sensible fluid losses refer to typical routes of excretion such as urination and defecation. Insensible losses refer to other routes of fluid loss, such as in sweat and from the respiratory tract. Fluid replacement goes beyond the normal physiologic losses and includes such conditions as vomiting, diarrhea, or severe cutaneous burns. One must consider these 2 categories of fluid loss separately when devising a fluid management strategy for an individual patient.

How to measure volume changes in a patient?

Weight: One of the most sensitive indicators of patient volume status changes is their body weight. Patient weight changes approximate a gold standard to determine fluid status. Unfortunately, due to differences in scales available to hospital staff, this can be a challenging target to measure. It is ideal to weigh a patient daily on the same scale to determine trends in weight changes. One can see weight gain in states of fluid excess and weight loss in states of fluid deficit. It is also helpful to look at patient records to see any recent outpatient visits before hospitalization, which might indicate a patient's normal baseline weight.

How many ml is 10 kg?

First 10 kg = 100 ml/kg/day x 10 kg = 1000 mL per day

What does it mean when your blood pressure drops?

Orthostatic vital signs: A drop of at least 20 mm Hg systolic blood pressure or 10 mm Hg diastolic blood pressure within 2 to 5 minutes of quiet standing after 5 minutes of supine rest indicates orthostatic hypotension. Dehydrated or elderly patients who have lost sensitivity in their baroreceptors in their blood vessels might display these findings.

How long does it take for a capillary to refill?

Capillary refill: Normally less than 2 seconds. Easy to test on fingertips and toes

Why are fluids used in surgery?

For example, fluids can be added to replace fluid losses ( e.g. vomiting, blood loss, water loss from the respiratory system) that occur before and during surgery. In addition, many sedatives and anesthetics will adversely affect the circulatory system, so fluids are used to provide hemodynamic support.

Why do you need fluids during anesthesia?

Fluids are administered to patients not only to replace fluid loss but also to correct electrolyte abnormalities, promote kidney diuresis, and maintain the tissue or organ perfusion rate while a patient is undergoing anesthesia. For example, fluids can be added to replace fluid losses ( e.g. vomiting, blood loss, water loss from the respiratory system) that occur before and during surgery. In addition, many sedatives and anesthetics will adversely affect the circulatory system, so fluids are used to provide hemodynamic support. If the patient's blood pressure goes below 60 mm Hg, some tissues and organs may see a decrease in perfusion. The body will protect certain important organs first, such as the lungs, heart, and brain. The kidney may see a decrease in perfusion, and acute renal failure can result from prolonged periods of extremely low blood pressure during anesthesia. This article focuses on dehydrated patients.

What is insensible loss?

Insensible losses are those that cannot be quantified ( e.g. cutaneous losses with fevers, respiratory tract losses such as in a panting dog, fluids lost in feces). The veterinarian will estimate the insensible losses and incorporate that into the total fluid rate.

Which compartment contains the most fluid?

The interstitial compartment contains three-quarters of all the fluid in the extracellular space. The intravascular compartment contains the fluid, mostly plasma, that is within the blood vessels. The fluid in the transcellular compartment is produced by specialized cells responsible for cerebrospinal fluid, gastrointestinal fluid, bile, glandular secretions, respiratory sections, and synovial fluids.1

How often should you measure urine production?

To be able to accurately measure urine production, a urinary catheter must be inserted and a collection system must be set up and emptied and measured every two to four hours. If inserting a urinary catheter is not an option, collect the urine via free catch or on a medical absorbent pad (a chuck pad).

How much fluid does a patient need to get caught up?

So, if the patient had been NPO for 12 hours, they would need 984 ml of fluid to get caught up (82 ml x 12 hours). This would typically be replaced over 3 hours. The first hour would be half the volume, while the second and third hours would replace the remaining volume in quarters. For example:

How many ml is a total?

Total = 82 ml. This would be the hourly needs of the patient.

Can fluids get away from you?

You’ll find out really quick that fluids can get away from you (either being ahead or behind in schedule). So to make things even more simple, its nice to have a running total. That way you know how much you should have already given at those intervals.

What is the most commonly used resuscitation formula?

Predominantly, fluid resuscitation is carried out intravenously and the most commonly used resuscitation formula is the pure crystalloid Parkland formula.

What happens when blood volume decreases?

Blood volume decreases, resulting in intravascular hypovolaemia – sometimes referred to as ‘burns shock’ – which can be fatal if left untreated.

Why is IV fluid important for burn patients?

Through clinical experience, we know that adequate volumes of IV fluids are required to prevent burns shock in those with extensive burn injuries . The aim of resuscitation is to restore and maintain adequate oxygen ...

How long does plasma leakage last after a burn?

The greatest loss of plasma occurs in the first 12 hours after burn injury. The plasma loss then slowly decreases during the second 12 hours of the post-burn phase, although extensive leakage can continue for up to three days (Ahrns, 2004). Optimal fluid replacement during this period is essential to ensure cardiac output and renal and tissue perfusion. Usually, 36 hours post-burn, capillary permeability returns to normal and fluid is drawn back into the circulation.

What fluid is used to prevent burn shock?

For many years, there was no consensus on the ideal fluid for preventing burn shock except that the essential ingredients should include water and salt . The formula to be followed is 0.5mmol sodium per kilogram of body weight per percentage of total burn surface area (TBSA).

How to find volume needed in Muir and Barclay?

The Muir and Barclay formula is as follows: % x kg = volume needed.

Is there scientific evidence for fluid resuscitation?

There is no robust scientific evidence to support the adoption of one particular protocol over any others. To date, no single formula recommendation has been established as the most successful approach to adopt on fluid resuscitation of burn patients who are critically ill.